Echmarcach Mac Ragnaill on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Echmarcach mac Ragnaill (died 1064/1065) was a dominant figure in the eleventh-century

Echmarcach was the son of a man named Ragnall. Whilst Echmarcach bore a

Echmarcach was the son of a man named Ragnall. Whilst Echmarcach bore a

Echmarcach appears to first emerge in the historical record in the first half of the eleventh century, when he was one of the three kings who met with Knútr Sveinnsson, ruler of the Anglo-Scandinavian Empire comprising the kingdoms of

Echmarcach appears to first emerge in the historical record in the first half of the eleventh century, when he was one of the three kings who met with Knútr Sveinnsson, ruler of the Anglo-Scandinavian Empire comprising the kingdoms of  Of the three kings, Máel Coluim appears to have been the most powerful, and it is possible that Mac Bethad and Echmarcach were underkings or clientkings of his. Mac Bethad appears to have become

Of the three kings, Máel Coluim appears to have been the most powerful, and it is possible that Mac Bethad and Echmarcach were underkings or clientkings of his. Mac Bethad appears to have become  Further confusion about Knútr in Scottish affairs comes from a continental source. At some point before about 1030, the eleventh-century '' Historiarum libri quinque'', by

Further confusion about Knútr in Scottish affairs comes from a continental source. At some point before about 1030, the eleventh-century '' Historiarum libri quinque'', by  The record of Echmarcach in company with Máel Coluim and Mac Bethad could indicate that he was in some sense a 'Scottish' ruler, and that his powerbase was located in the Isles. Such an orientation could add weight to the possibility that Echmarcach was descended from Ragnall mac Gofraid. As for Máel Coluim, his influence in the Isles may be evidenced by the twelfth-century ''

The record of Echmarcach in company with Máel Coluim and Mac Bethad could indicate that he was in some sense a 'Scottish' ruler, and that his powerbase was located in the Isles. Such an orientation could add weight to the possibility that Echmarcach was descended from Ragnall mac Gofraid. As for Máel Coluim, his influence in the Isles may be evidenced by the twelfth-century ''

The rationale behind the meeting of the four kings is uncertain. One possibility is that it was related to Máel Coluim's annexation of Lothian, a region that likely encompassed an area roughly similar to the modern boundaries of

The rationale behind the meeting of the four kings is uncertain. One possibility is that it was related to Máel Coluim's annexation of Lothian, a region that likely encompassed an area roughly similar to the modern boundaries of  It is possible that Knútr took other actions to contain Orkney. Evidence that Knútr installed Hákon as overlord of the Isles may be preserved by the twelfth-century '' Ágrip af Nóregskonungasǫgum''. The historicity of this event is uncertain, however, and Hákon's authority in the Isles is not attested by any other source. Be that as it may, this twelfth-century text states that Hákon had been sent into the Isles by Óláfr, and that Hákon ruled the region for the rest of his life. The chronology outlined by this source suggests that Hákon left Norway at about the time Óláfr assumed the kingship in 1016. The former is certainly known to have been in Knútr's service soon afterwards in England. One possibility is that Knútr installed Hákon as overlord of Orkney and the Isles in about 1016/1017, before handing him possession of the Earldom of Worcester in about 1017. If this was the case, Hákon would have been responsible for not only a strategic part of the Anglo-Welsh frontier, but also accountable for the far-reaching sea-lanes that stretched from the Irish Sea region to Norway. It seems likely that Knútr was more concerned about Orkney and the Isles, and the security of the sea-lanes around Scotland, than surviving sources let on. Crawford (2013). Hákon's death at sea would have certainly been a cause of concern for Knútr's regime, and could have been directly responsible to the meeting between him and the three kings. If Hákon had indeed possessed overlordship of the Isles, his demise could well have paved the way for Echmarcach's own rise to power. Having come to terms with the three kings, it is possible that Knútr relied upon Echmarcach to counter the ambitions of the Orcadians, who could have attempted to seize upon Hákon's fall and renew their influence in the Isles.

It is possible that Knútr took other actions to contain Orkney. Evidence that Knútr installed Hákon as overlord of the Isles may be preserved by the twelfth-century '' Ágrip af Nóregskonungasǫgum''. The historicity of this event is uncertain, however, and Hákon's authority in the Isles is not attested by any other source. Be that as it may, this twelfth-century text states that Hákon had been sent into the Isles by Óláfr, and that Hákon ruled the region for the rest of his life. The chronology outlined by this source suggests that Hákon left Norway at about the time Óláfr assumed the kingship in 1016. The former is certainly known to have been in Knútr's service soon afterwards in England. One possibility is that Knútr installed Hákon as overlord of Orkney and the Isles in about 1016/1017, before handing him possession of the Earldom of Worcester in about 1017. If this was the case, Hákon would have been responsible for not only a strategic part of the Anglo-Welsh frontier, but also accountable for the far-reaching sea-lanes that stretched from the Irish Sea region to Norway. It seems likely that Knútr was more concerned about Orkney and the Isles, and the security of the sea-lanes around Scotland, than surviving sources let on. Crawford (2013). Hákon's death at sea would have certainly been a cause of concern for Knútr's regime, and could have been directly responsible to the meeting between him and the three kings. If Hákon had indeed possessed overlordship of the Isles, his demise could well have paved the way for Echmarcach's own rise to power. Having come to terms with the three kings, it is possible that Knútr relied upon Echmarcach to counter the ambitions of the Orcadians, who could have attempted to seize upon Hákon's fall and renew their influence in the Isles.

Following his meeting with Knútr, Echmarcach appears to have allied himself with the

Following his meeting with Knútr, Echmarcach appears to have allied himself with the  At about the time of his union with Cacht, Donnchad aspired to become

At about the time of his union with Cacht, Donnchad aspired to become  In 1036, Echmarcach replaced Amlaíb Cuarán's son, Sitriuc mac Amlaíb, as King of Dublin. The ''Annals of Tigernach'' specifies that Sitriuc fled overseas as Echmarcach took control. An alliance with Donnchad could explain Echmarcach's success in seizing the kingship from Sitriuc. Although Donnchad and Sitriuc were maternal half-brothers—as both descended from Gormlaith ingen Murchada—Donnchad's hostility towards Sitriuc is demonstrated by the record of a successful attack he led upon the Dubliners in 1026.

Another factor behind Echmarcach's actions against Sitriuc could concern Knútr. Echmarcach's seizure of Dublin occurred only a year after the latter's death in 1035. Downham (2004) pp. 63–65. There appears to be

In 1036, Echmarcach replaced Amlaíb Cuarán's son, Sitriuc mac Amlaíb, as King of Dublin. The ''Annals of Tigernach'' specifies that Sitriuc fled overseas as Echmarcach took control. An alliance with Donnchad could explain Echmarcach's success in seizing the kingship from Sitriuc. Although Donnchad and Sitriuc were maternal half-brothers—as both descended from Gormlaith ingen Murchada—Donnchad's hostility towards Sitriuc is demonstrated by the record of a successful attack he led upon the Dubliners in 1026.

Another factor behind Echmarcach's actions against Sitriuc could concern Knútr. Echmarcach's seizure of Dublin occurred only a year after the latter's death in 1035. Downham (2004) pp. 63–65. There appears to be  If Echmarcach was a member of the Waterford dynasty, his action against Sitriuc may have been undertaken in the context of continuous dynastic strife between Dublin and Waterford in the tenth- and eleventh centuries. This could mean that Echmarcach's expulsion of Sitriuc was a direct act of vengeance for the latter's slaying of Ragnall ua Ímair (then King of Waterford) the year before.

Little is known of Echmarcach's short reign in Dublin other than an attack on

If Echmarcach was a member of the Waterford dynasty, his action against Sitriuc may have been undertaken in the context of continuous dynastic strife between Dublin and Waterford in the tenth- and eleventh centuries. This could mean that Echmarcach's expulsion of Sitriuc was a direct act of vengeance for the latter's slaying of Ragnall ua Ímair (then King of Waterford) the year before.

Little is known of Echmarcach's short reign in Dublin other than an attack on

The evidence of Þórfinnr's power in the Isles could suggest that he possessed an active interest in the ongoing struggle over the Dublin kingship. Þórfinnr's predatory operations in the Irish Sea region may have contributed to Echmarcach's loss of Dublin in 1038. Hudson, BT (2005) p. 135. Just as Echmarcach may have seized upon Knútr's demise to expand, it is possible that the vacuum caused by Knútr's death allowed Þórfinnr to prey upon the Irish Sea region. Certainly, the corresponding annal-entry of the ''Annals of Tigernach''—stating that

The evidence of Þórfinnr's power in the Isles could suggest that he possessed an active interest in the ongoing struggle over the Dublin kingship. Þórfinnr's predatory operations in the Irish Sea region may have contributed to Echmarcach's loss of Dublin in 1038. Hudson, BT (2005) p. 135. Just as Echmarcach may have seized upon Knútr's demise to expand, it is possible that the vacuum caused by Knútr's death allowed Þórfinnr to prey upon the Irish Sea region. Certainly, the corresponding annal-entry of the ''Annals of Tigernach''—stating that  During his second reign, Echmarcach may have been involved in military activities in Wales with Gruffudd ap Rhydderch. For instance in the year 1049, English and Welsh sources record that Norse-Gaelic forces were utilised by Gruffudd ap Rhydderch against his Welsh rivals and English neighbours. Specifically, the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'', the thirteenth- and fourteenth-century ''

During his second reign, Echmarcach may have been involved in military activities in Wales with Gruffudd ap Rhydderch. For instance in the year 1049, English and Welsh sources record that Norse-Gaelic forces were utilised by Gruffudd ap Rhydderch against his Welsh rivals and English neighbours. Specifically, the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'', the thirteenth- and fourteenth-century ''

In 1052, Diarmait drove Echmarcach from Dublin. Wadden (2015) p. 32; Charles-Edwards (2013) pp. 528, 564, 573; Downham (2013a) p. 164; Duffy (2006) p. 55; Hudson, B (2005); Hudson, BT (2004a); Duffy (2002) p. 53; Duffy (1998) p. 76; Duffy (1997) p. 37; Duffy (1993a) p. 32; Duffy (1993b); Duffy (1992) pp. 94, 96–97; Candon (1988) pp. 399, 401; Anderson (1922a) pp. 590–592 n. 2. The event is documented by the ''Annals of the Four Masters'', the ''Annals of Tigernach'', the ''Annals of Ulster'', and ''Chronicon Scotorum''. These annalistic accounts indicate that, although Diarmait's conquest evidently began with a mere raid upon Fine Gall, this action further escalated into the seizure of Dublin itself. Following several skirmishes fought around the town's central fortress, the aforesaid accounts report that Echmarcach fled overseas, whereupon Diarmait assumed the kingship. With Diarmait's conquest, Norse-Gaelic Dublin ceased to be an independent power in Ireland; and when Diarmait and his son, Murchad, died about twenty years later, Irish rule had been exercised over Fine Gall and Dublin in a degree unheard of before. In consequence of Echmarcach's expulsion, Dublin effectively became the provincial capital of Leinster, with the town's remarkable wealth and military power at Diarmait's disposal.

In 1052, Diarmait drove Echmarcach from Dublin. Wadden (2015) p. 32; Charles-Edwards (2013) pp. 528, 564, 573; Downham (2013a) p. 164; Duffy (2006) p. 55; Hudson, B (2005); Hudson, BT (2004a); Duffy (2002) p. 53; Duffy (1998) p. 76; Duffy (1997) p. 37; Duffy (1993a) p. 32; Duffy (1993b); Duffy (1992) pp. 94, 96–97; Candon (1988) pp. 399, 401; Anderson (1922a) pp. 590–592 n. 2. The event is documented by the ''Annals of the Four Masters'', the ''Annals of Tigernach'', the ''Annals of Ulster'', and ''Chronicon Scotorum''. These annalistic accounts indicate that, although Diarmait's conquest evidently began with a mere raid upon Fine Gall, this action further escalated into the seizure of Dublin itself. Following several skirmishes fought around the town's central fortress, the aforesaid accounts report that Echmarcach fled overseas, whereupon Diarmait assumed the kingship. With Diarmait's conquest, Norse-Gaelic Dublin ceased to be an independent power in Ireland; and when Diarmait and his son, Murchad, died about twenty years later, Irish rule had been exercised over Fine Gall and Dublin in a degree unheard of before. In consequence of Echmarcach's expulsion, Dublin effectively became the provincial capital of Leinster, with the town's remarkable wealth and military power at Diarmait's disposal.

The fact that in 1054, Ímar mac Arailt is styled on his death "''rí Gall''", a title meaning "king of the foreigners", could indicate that Diarmait reinserted him as King of Dublin after Echmarcach's expulsion. Murchad appears to have been granted the kingship by 1059, as evidenced by the title ''tigherna Gall'', meaning "lord of the foreigners", accorded to him that year. Murchad was evidently an energetic figure, and in 1061 he launched a successful seaborne invasion of Mann. The ''Annals of the Four Masters'', and the ''Annals of Tigernach'' further reveal that Murchad extracted a tax from Mann, and that the son of a certain Ragnall (literally "''mac Raghnaill''" and "''mac Ragnaill''") was driven from the island. The gathering of ''cáin'' or tribute was a mediaeval right of kingship in Ireland. In fact, Murchad's collection of such tribute from the Manx could be evidence that, as the King of Dublin, Murchad regarded himself as the rightful overlord of Mann. If the vanquished son of Ragnall was Echmarcach himself, as seems most likely, the record of Murchad's actions against him would appear to indicate that Echmarcach had seated himself on the island after his expulsion from Dublin. Another possibility is that Echmarcach had only been reestablished himself as king in the Isles after Ímar mac Arailt's death in 1054.

The fact that in 1054, Ímar mac Arailt is styled on his death "''rí Gall''", a title meaning "king of the foreigners", could indicate that Diarmait reinserted him as King of Dublin after Echmarcach's expulsion. Murchad appears to have been granted the kingship by 1059, as evidenced by the title ''tigherna Gall'', meaning "lord of the foreigners", accorded to him that year. Murchad was evidently an energetic figure, and in 1061 he launched a successful seaborne invasion of Mann. The ''Annals of the Four Masters'', and the ''Annals of Tigernach'' further reveal that Murchad extracted a tax from Mann, and that the son of a certain Ragnall (literally "''mac Raghnaill''" and "''mac Ragnaill''") was driven from the island. The gathering of ''cáin'' or tribute was a mediaeval right of kingship in Ireland. In fact, Murchad's collection of such tribute from the Manx could be evidence that, as the King of Dublin, Murchad regarded himself as the rightful overlord of Mann. If the vanquished son of Ragnall was Echmarcach himself, as seems most likely, the record of Murchad's actions against him would appear to indicate that Echmarcach had seated himself on the island after his expulsion from Dublin. Another possibility is that Echmarcach had only been reestablished himself as king in the Isles after Ímar mac Arailt's death in 1054.

In 1055, after being outlawed for treason in the course of a comital power-struggle, English nobleman Ælfgar Leofricson fled from England to Ireland. Ælfgar evidently received considerable military aid from the Irish to form a fleet of eighteen ships, and together with Gruffudd ap Llywelyn, King of Gwynedd and Deheubarth invaded

In 1055, after being outlawed for treason in the course of a comital power-struggle, English nobleman Ælfgar Leofricson fled from England to Ireland. Ælfgar evidently received considerable military aid from the Irish to form a fleet of eighteen ships, and together with Gruffudd ap Llywelyn, King of Gwynedd and Deheubarth invaded  Ælfgar's Irish confederate of 1055 is not identified in any source, and it is not clear that Diarmait had a part to play in the aforesaid events of that year. In fact, it is possible that Ælfgar received aid not from Diarmait, but from Donnchad—Diarmait's enemy and Echmarcach's associate—a man who then controlled the Norse-Gaelic enclaves of

Ælfgar's Irish confederate of 1055 is not identified in any source, and it is not clear that Diarmait had a part to play in the aforesaid events of that year. In fact, it is possible that Ælfgar received aid not from Diarmait, but from Donnchad—Diarmait's enemy and Echmarcach's associate—a man who then controlled the Norse-Gaelic enclaves of

In 1064, Echmarcach seems to have accompanied by Donnchad upon a

In 1064, Echmarcach seems to have accompanied by Donnchad upon a  Marianus Scotus' account of Echmarcach accords him the Latin title "''rex Innarenn''". On one hand, this may be a garbled form of the Latin "''rex insularum''", meaning "King of the Isles". If so, the titles "''ri Gall''" and "''rí Gall''" accorded to him by the ''Annals of Ulster'' and the ''Annals of Inisfallen'' in 1064 could indicate that he was still regarded as ruler of Mann. On the other hand, "''rex Innarenn''" could instead mean "

Marianus Scotus' account of Echmarcach accords him the Latin title "''rex Innarenn''". On one hand, this may be a garbled form of the Latin "''rex insularum''", meaning "King of the Isles". If so, the titles "''ri Gall''" and "''rí Gall''" accorded to him by the ''Annals of Ulster'' and the ''Annals of Inisfallen'' in 1064 could indicate that he was still regarded as ruler of Mann. On the other hand, "''rex Innarenn''" could instead mean "

Echmarcach has sometimes been identified as a certain Margaðr who appears in various mediaeval sources documenting the contemporary Irish Sea adventures of Margaðr and Guthormr Gunnhildarson. One such source is ''

Echmarcach has sometimes been identified as a certain Margaðr who appears in various mediaeval sources documenting the contemporary Irish Sea adventures of Margaðr and Guthormr Gunnhildarson. One such source is '' The fateful encounter between Margaðr and Guthormr is sometimes dated to 1052 on the presumption that Margaðr is identical to Echmarcach, and that the event must have taken place at the conclusion of Echmarcach's second reign in Dublin. In fact, the

The fateful encounter between Margaðr and Guthormr is sometimes dated to 1052 on the presumption that Margaðr is identical to Echmarcach, and that the event must have taken place at the conclusion of Echmarcach's second reign in Dublin. In fact, the

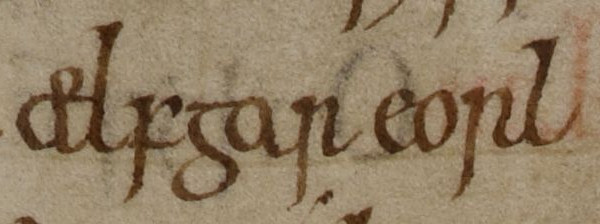

Iehmarc 1 (Male)

at

Irish Sea

The Irish Sea or , gv, Y Keayn Yernagh, sco, Erse Sie, gd, Muir Èireann , Ulster-Scots: ''Airish Sea'', cy, Môr Iwerddon . is an extensive body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the Ce ...

region. At his height, he reigned as king over Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

, the Isles, and perhaps the Rhinns of Galloway

The Rhins of Galloway, otherwise known as the Rhins of Wigtownshire (or as The Rhins, also spelt The Rhinns; gd, Na Rannaibh), is a hammer-head peninsula in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland. Stretching more than from north to south, its southern ...

. The precise identity of Echmarcach's father, Ragnall, is uncertain. One possibility is that this man was one of two eleventh-century rulers of Waterford

"Waterford remains the untaken city"

, mapsize = 220px

, pushpin_map = Ireland#Europe

, pushpin_map_caption = Location within Ireland##Location within Europe

, pushpin_relief = 1

, coordinates ...

. Another possibility is that Echmarcach's father was an early eleventh-century ruler of the Isles. If any of these identifications are correct, Echmarcach may have been a member of the Uí Ímair

The Uí Ímair (; meaning ‘''scions of Ivar’''), also known as the Ivar Dynasty or Ivarids was a royal Norse-Gael dynasty which ruled much of the Irish Sea region, the Kingdom of Dublin, the western coast of Scotland, including the Hebrides ...

kindred.

Echmarcach first appears on record in about 1031, when he was one of three kings in northern Britain who submitted to Knútr Sveinnsson, ruler of the Anglo-Scandinavian Empire. Echmarcach is recorded to have ruled over Dublin in 1036–1038 and 1046–1052. After losing Dublin for the final time, he appears to have been seated in the Isles on Mann. In 1061, about a decade after his final defeat in Dublin, Echmarcach appears to have been expelled from the Isles, and may have then fallen back into Galloway.

Echmarcach appears to have forged an alliance with the powerful Uí Briain

The O'Brien dynasty ( ga, label= Classical Irish, Ua Briain; ga, label=Modern Irish, Ó Briain ; genitive ''Uí Bhriain'' ) is a noble house of Munster, founded in the 10th century by Brian Boru of the Dál gCais (Dalcassians). After becomi ...

. A leading member of this kindred, Donnchad mac Briain, King of Munster Donnchadh () is a masculine given name common to the Irish and Scottish Gaelic languages. It is composed of the elements ''donn'', meaning "brown" or "dark" from Donn a Gaelic God; and ''chadh'', meaning "chief" or "noble". The name is also written ...

, was married to Cacht ingen Ragnaill

Cacht ingen Ragnaill was the queen of Donnchad mac Briain, from their marriage in 1032 to her death in 1054, when she is styled Queen of Ireland in the Irish annals of the Clonmacnoise group: the Annals of Tigernach and Chronicon Scotorum. Her h ...

, a woman who could have been closely related to Echmarcach. Certainly, Echmarcach's daughter, Mór, married one of Donnchad's Uí Briain close kinsmen. Echmarcach's violent career brought him into bitter conflict with a particular branch of the Uí Ímair who had held Dublin periodically from the early eleventh century. This branch was supported by the rising Uí Cheinnselaig, an Irish kindred responsible for Echmarcach's final expulsion from Dublin and apparently Mann as well.

In about 1064, having witnessed much of his formerly expansive sea-kingdom fall into the hands of the Uí Cheinnselaig, Echmarcach accompanied Donnchad—a man who was himself deposed—upon a pilgrimage to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

. Possibly aged about sixty-five at this point in his life, it was here that Echmarcach died, in either 1064 or 1065. In the decades following his demise, the Uí Briain used Echmarcach's descendants as a means to dominate and control Dublin and the Isles. One of his grandsons eventually ruled as king.

Uncertain parentage

Echmarcach was the son of a man named Ragnall. Whilst Echmarcach bore a

Echmarcach was the son of a man named Ragnall. Whilst Echmarcach bore a Gaelic

Gaelic is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". As a noun it refers to the group of languages spoken by the Gaels, or to any one of the languages individually. Gaelic languages are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, and Ca ...

name, the name of his father is ultimately derived from Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and t ...

, a fact that serves to exemplify the hybrid nature of the eleventh-century Irish Sea

The Irish Sea or , gv, Y Keayn Yernagh, sco, Erse Sie, gd, Muir Èireann , Ulster-Scots: ''Airish Sea'', cy, Môr Iwerddon . is an extensive body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the Ce ...

region, The identity of Echmarcach's father is uncertain. Woolf (2007) p. 246. One possibility is that Ragnall was a member of the dynasty that ruled the Norse-Gaelic enclave of Waterford

"Waterford remains the untaken city"

, mapsize = 220px

, pushpin_map = Ireland#Europe

, pushpin_map_caption = Location within Ireland##Location within Europe

, pushpin_relief = 1

, coordinates ...

in tenth- and eleventh centuries. If so, Echmarcach may have been the son of one of two Waterfordian rulers: Ragnall mac Ímair, King of Waterford, or this man's apparent son, Ragnall ua Ímair, King of Waterford

Ragnall ua Ímair (died 1035), also known as Ragnall mac Ragnaill, was an eleventh-century King of Waterford. He appears to have ruled as king from 1022 to 1035, the year of his death.

Family

Ragnall seems to have been a descendant of Ím ...

. Another possibility is that Echmarcach belonged to a family from the Isles, and that his father was Ragnall mac Gofraid, King of the Isles

Ragnall is a village and civil parish in Nottinghamshire, England. At the time of the 2001 census it had a population of 102, increasing to 146 at the 2011 census. It is located on the A57 road one mile west of the River Trent. The parish churc ...

, son and possible successor of Gofraid mac Arailt, King of the Isles

Gofraid mac Arailt (died 989), in Old Norse Guðrøðr Haraldsson , was a Scandinavian or Norse-Gael king. He and his brother Maccus were active in the lands around the Irish Sea in the 970s and 980s.

Origins

Gofraid and Maccus are usually assume ...

. As a descendant of either of the aforesaid families, Echmarcach would appear to have been a member of the Uí Ímair

The Uí Ímair (; meaning ‘''scions of Ivar’''), also known as the Ivar Dynasty or Ivarids was a royal Norse-Gael dynasty which ruled much of the Irish Sea region, the Kingdom of Dublin, the western coast of Scotland, including the Hebrides ...

, a royal dynasty descended from the Scandinavian sea-king Ímar

Ímar ( non, Ívarr ; died c. 873), who may be synonymous with Ivar the Boneless, was a Viking leader in Ireland and Scotland in the mid-late ninth century who founded the Uí Ímair dynasty, and whose descendants would go on to dominate the Iri ...

.

Echmarcach and the imperium of Knútr Sveinnsson

Knútr and the three kings

Echmarcach appears to first emerge in the historical record in the first half of the eleventh century, when he was one of the three kings who met with Knútr Sveinnsson, ruler of the Anglo-Scandinavian Empire comprising the kingdoms of

Echmarcach appears to first emerge in the historical record in the first half of the eleventh century, when he was one of the three kings who met with Knútr Sveinnsson, ruler of the Anglo-Scandinavian Empire comprising the kingdoms of Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark

...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, and Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

. The event itself is noted by ''Knútsdrápa ''Knútsdrápur'' (plural of ''Knútsdrápa'') are Old Norse skaldic compositions in the form of '' drápur'' which were recited for the praise of Canute the Great. There are a number of these:

* The '' Knútsdrápa'' by Óttarr svarti

* The ''Kn ...

'', a contemporary ''drápa

A skald, or skáld (Old Norse: , later ; , meaning "poet"), is one of the often named poets who composed skaldic poetry, one of the two kinds of Old Norse poetry, the other being Eddic poetry, which is anonymous. Skaldic poems were traditionally ...

'' composed by Sigvatr Þórðarson

Sigvatr Þórðarson or Sighvatr Þórðarson or Sigvat the Skald (995–1045) was an Icelandic skald. He was a court poet to King Olaf II of Norway, as well as Canute the Great, Magnus the Good and Anund Jacob, by whose reigns his floruit ca ...

, an eleventh-century Icelandic skald

A skald, or skáld (Old Norse: , later ; , meaning "poet"), is one of the often named poets who composed skaldic poetry, one of the two kinds of Old Norse poetry, the other being Eddic poetry, which is anonymous. Skaldic poems were traditionally ...

. Although Sigvatr's composition fails to identify the three kings by name, it does reveal that Knútr met them in Fife

Fife (, ; gd, Fìobha, ; sco, Fife) is a council area, historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland. It is situated between the Firth of Tay and the Firth of Forth, with inland boundaries with Perth and Kinross (i ...

. The ninth- to twelfth-century ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the ''Chronicle'' was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alf ...

'' also notes the meeting. The "D" version of the chronicle records that Knútr went to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

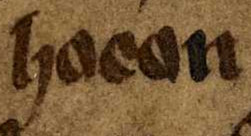

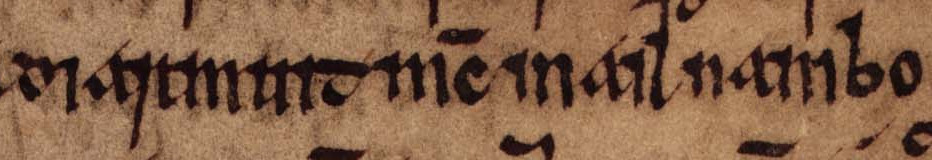

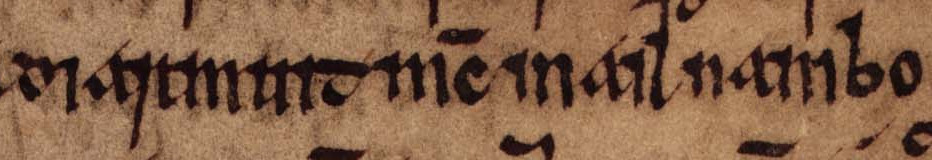

in 1031, and soon after travelled to Scotland where he received the submission of an unnamed Scottish king. The later "E" version provides more information, stating that, after his return from Rome in 1031, Knútr went to Scotland and received the submission of three kings named: "''Mælcolm''", "''Mælbæþe''", and "''Iehmarc''". The latter name appears to be a phonetic form of the Gaelic '' Echmarcach'', a relatively uncommon name. The three men almost certainly refer to: Máel Coluim mac Cináeda, King of Scotland, Mac Bethad mac Findlaích

Macbeth ( – 15 August 1057) was King of Scots from 1040 until his death. He ruled over the Kingdom of Alba, which covered only a portion of present-day Scotland.

Little is known about Macbeth's early life, although he was the son of Findláe ...

, and Echmarcach himself.

Of the three kings, Máel Coluim appears to have been the most powerful, and it is possible that Mac Bethad and Echmarcach were underkings or clientkings of his. Mac Bethad appears to have become

Of the three kings, Máel Coluim appears to have been the most powerful, and it is possible that Mac Bethad and Echmarcach were underkings or clientkings of his. Mac Bethad appears to have become Mormaer of Moray

The title Earl of Moray, Mormaer of Moray or King of Moray was originally held by the rulers of the Province of Moray, which existed from the 10th century with varying degrees of independence from the Kingdom of Alba to the south. Until 1130 th ...

in 1032 after the slaying of his kinsman, Gilla Comgáin mac Máel Brigti, Mormaer of Moray. Previous rulers of Moray are sometimes styled as kings by various Irish annals, a fact which may explain why Mac Bethad was called a king when he met Knútr. Although the apparent date of Mac Bethad's accession to the mormaership (1032) appears to contradict the date of the kings' meeting (1031), this discrepancy can be accounted for in two ways. One possibility is that Gilla Comgáin was actually slain in 1031 but only recorded in 1032. Another possibility is that Knútr merely returned from Rome in 1031, but actually met with the kings in 1032, after Gilla Comgáin's demise and Mac Bethad's accession. There is further evidence that could cast doubt on the date of the meeting. Although the aforesaid versions of the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' date Knútr's pilgrimage to 1031, he is otherwise known to have visited Rome in 1027. Whilst it is possible he undertook two pilgrimages during his career, it is more likely that the chronicle has misdated his journey. In fact, it possible that the chronicle failed to account for the time in which Knútr spent on the continent and Scandinavia after having visited Rome.

Further confusion about Knútr in Scottish affairs comes from a continental source. At some point before about 1030, the eleventh-century '' Historiarum libri quinque'', by

Further confusion about Knútr in Scottish affairs comes from a continental source. At some point before about 1030, the eleventh-century '' Historiarum libri quinque'', by Rodulfus Glaber Rodulfus, or Raoul Glaber (which means "the Smooth" or "the Bald") (985–1047), was an 11th-century Benedictine chronicler.

Life

Glaber was born in 985 in Burgundy. At the behest of his uncle, a monk at Saint-Léger-de-Champeaux, Glaber was sent ...

, records that Knútr fought a long campaign against Máel Coluim, and that hostilities were finally brought to a close by the intervention of Knútr's wife, Emma, and her brother, Richard II, Duke of Normandy

Richard II (died 28 August 1026), called the Good (French: ''Le Bon''), was the duke of Normandy from 996 until 1026.

Life

Richard was the eldest surviving son and heir of Richard the Fearless and Gunnor. He succeeded his father as the ruler of ...

. If Rodulfus' account is to be believed, this conflict must have taken place before Richard's death in 1026, and could refer to events surrounding Máel Coluim's violent annexation of Lothian

Lothian (; sco, Lowden, Loudan, -en, -o(u)n; gd, Lodainn ) is a region of the Scottish Lowlands, lying between the southern shore of the Firth of Forth and the Lammermuir Hills and the Moorfoot Hills. The principal settlement is the Sco ...

early in Knútr's reign. Lawson (2013); Lawson (1993) pp. 104–105. Despite uncertainties surrounding the reliability of Rodulfus' version of events, unless the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' has misdated Knútr's meeting in Scotland, Rodulfus' account could be evidence that Knútr involved himself with Scottish affairs before and after 1026.

The record of Echmarcach in company with Máel Coluim and Mac Bethad could indicate that he was in some sense a 'Scottish' ruler, and that his powerbase was located in the Isles. Such an orientation could add weight to the possibility that Echmarcach was descended from Ragnall mac Gofraid. As for Máel Coluim, his influence in the Isles may be evidenced by the twelfth-century ''

The record of Echmarcach in company with Máel Coluim and Mac Bethad could indicate that he was in some sense a 'Scottish' ruler, and that his powerbase was located in the Isles. Such an orientation could add weight to the possibility that Echmarcach was descended from Ragnall mac Gofraid. As for Máel Coluim, his influence in the Isles may be evidenced by the twelfth-century ''Prophecy of Berchán

In religion, a prophecy is a message that has been communicated to a person (typically called a ''prophet'') by a supernatural entity. Prophecies are a feature of many cultures and belief systems and usually contain divine will or law, or pre ...

'', which could indicate that he resided or exerted power in the Hebrides, specifically on the Inner Hebridean islands of Arran and Islay

Islay ( ; gd, Ìle, sco, Ila) is the southernmost island of the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. Known as "The Queen of the Hebrides", it lies in Argyll just south west of Jura, Scotland, Jura and around north of the Northern Irish coast. The isl ...

. Further evidence of Máel Coluim's influence in the Isles may be preserved by the fifteenth- to sixteenth-century ''Annals of Ulster

The ''Annals of Ulster'' ( ga, Annála Uladh) are annals of medieval Ireland. The entries span the years from 431 AD to 1540 AD. The entries up to 1489 AD were compiled in the late 15th century by the scribe Ruaidhrí Ó Luinín, ...

'' and the fourteenth-century ''Annals of Tigernach

The ''Annals of Tigernach'' ( abbr. AT, ga, Annála Tiarnaigh) are chronicles probably originating in Clonmacnoise, Ireland. The language is a mixture of Latin and Old and Middle Irish.

Many of the pre-historic entries come from the 12th-cent ...

'' which record the death of a certain Suibne mac Cináeda in 1034. These particular sources style Suibne "" and "". The Gaelic (plural ) is primarily a linguistic term referring to speakers of Gaelic. The Gaelic term , literally meaning "Stranger-", was attributed to the population of mixed Scandinavian and Gaelic ethnicity in the Hebrides. The fact that Máel Coluim and Suibne died the same year and share patronyms could be evidence that they were brothers. If the two were indeed closely related, Suibne may have been set up by Máel Coluim as a subordinate in an area of Scandinavian settlement. One possibility is that the account of Máel Coluim preserved by the ''Prophecy of Berchán'' could be evidence that this region encompassed the lands surrounding Kintyre

Kintyre ( gd, Cinn Tìre, ) is a peninsula in western Scotland, in the southwest of Argyll and Bute. The peninsula stretches about , from the Mull of Kintyre in the south to East and West Loch Tarbert in the north. The region immediately north ...

and the Outer Clyde Clyde may refer to:

People

* Clyde (given name)

* Clyde (surname)

Places

For townships see also Clyde Township

Australia

* Clyde, New South Wales

* Clyde, Victoria

* Clyde River, New South Wales

Canada

* Clyde, Alberta

* Clyde, Ontario, a tow ...

. This source, combined with the other accounts of Knútr's meeting, could indicate that Máel Coluim was then overlord of the Isles.

Context of the concordat with Knútr

The rationale behind the meeting of the four kings is uncertain. One possibility is that it was related to Máel Coluim's annexation of Lothian, a region that likely encompassed an area roughly similar to the modern boundaries of

The rationale behind the meeting of the four kings is uncertain. One possibility is that it was related to Máel Coluim's annexation of Lothian, a region that likely encompassed an area roughly similar to the modern boundaries of Berwickshire

Berwickshire ( gd, Siorrachd Bhearaig) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area in south-eastern Scotland, on the English border. Berwickshire County Council existed from 1890 until 1975, when the area became part of th ...

, East Lothian

East Lothian (; sco, East Lowden; gd, Lodainn an Ear) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland, as well as a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area. The county was called Haddingtonshire until 1921.

In 1975, the histo ...

, and possibly parts of Mid Lothian

Midlothian (; gd, Meadhan Lodainn) is a counties of Scotland, historic county, registration county, lieutenancy areas of Scotland, lieutenancy area and one of 32 council areas of Scotland used for local government. Midlothian lies in the eas ...

. The considerable span of years between this conquest and Knútr's meeting, however, could suggest that there were other factors. There appears to be evidence that the violent regime change in Moray (which enabled Mac Bethad to assume the mormaership) prompted Knútr to meet with the kings. Echmarcach and Máel Coluim may thus have been bound to keep the peace with Mac Bethad's troubled lordship. Certainly, the accounts of the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' record that Knútr met the kings in "Scotland", a region that likely refers to land north of Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth () is the estuary, or firth, of several Scottish rivers including the River Forth. It meets the North Sea with Fife on the north coast and Lothian on the south.

Name

''Firth'' is a cognate of ''fjord'', a Norse word meani ...

. Woolf (2007) pp. 247–248. Another possibility is that Máel Coluim aimed to gain Knútr's neutrality in a Scottish campaign against Mac Bethad, and sought naval support from Echmarcach himself. The absence of the King of Strathclyde

The list of the kings of Strathclyde concerns the kings of Alt Clut, later Strathclyde, a Brythonic kingdom in what is now western Scotland.

The kingdom was ruled from Dumbarton Rock, ''Alt Clut'', the Brythonic name of the rock, until around ...

from the assembled kings, and the possibility that Echmarcach's powerbase was situated somewhere in the Isles beyond Kintyre, could indicate that Knútr's main focus was on the troubled region of Moray, and the rulers whose lands it bordered. Another possibility is that the nonappearance of a Strathclyde representative is evidence that this Cumbrian realm had been recently annexed by the Scots which in turn drew a response from Knútr.

Knútr may have sought the submission of the assembled kings in an attempt to protect his northern borders. Additionally, he may have sought to prevent these kings from allowing military aid to reach potential challengers to his authority. If Echmarcach's father was indeed a son of Ragnall mac Gofraid, it would have meant that he was a nephew of Lagmann mac Gofraid. The latter was closely associated with Óláfr Haraldsson, and together both lent military assistance to Richard II in the early eleventh century. Wadden (2015) pp. 31–32; Downham (2004) p. 65. There is also evidence to suggest that the predecessors of Ragnall mac Gofraid and Lagmann possessed connections with the Normans. In consequence, there is reason to suspect that Knútr sought to counter a potential association between Echmarcach and Richard II. Knútr and Óláfr were certainly at odds. In 1028, only a few years before the meeting of kings, Knútr seized control of Norway after defeating Óláfr. Knútr proceeded to appoint his own nephew, Hákon Eiríksson

Haakon Ericsson (Old Norse: ''Hákon Eiríksson''; no, Håkon Eiriksson; died c. 1029–1030) was the last Earl of Lade and governor of Norway from 1012 to 1015 and again from 1028 to 1029 as a vassal under Danish King Knut the Great.

Biograph ...

, as regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

in Norway. Unfortunately for Knútr, Hákon perished at sea in late 1029 or early 1030. About three years later, Knútr's overlordship in Norway was challenged by a certain Tryggvi Óláfsson. Hollander (2011) pp. 535–536 ch. 249; Bolton (2009) p. 147; Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 124–125; Hudson, B (1994) pp. 333–334; Hudson, BT (1992) p. 359; Jónsson (1908a) p. 247; Jónsson (1908b) p. 231. This man seemingly possessed connections with Dublin and the Isles, as saga-tradition appears to reveal that his mother, Gyða, was a daughter of Amlaíb Cuarán. Although Tryggvi apparently enjoyed considerable local support when he landed in Norway in about 1033, he was nonetheless overwhelmed by forces loyal to Knútr and killed. Tryggvi is unlikely to have been Knútr's only challenger, and the episode itself evinces the way in which potential threats to Knútr could emerge from the Scandinavian settlements in Britain and Ireland.

Close connections between the rulers of Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

and the family of Óláfr may well have posed a potential threat to Knútr. The concordat between Knútr and the three kings could, therefore, have been a calculated attempt to disrupt the spread of Orcadian power, and an attempt to block possible Orcadian intervention into Norway. Specifically, Knútr may have wished to curb the principal Orcadian, Þórfinnr Sigurðarson, Earl of Orkney

Thorfinn Sigurdsson (1009?– 1065), also known as Thorfinn the Mighty (Old Norse: ''Þorfinnr inn riki''), was an 11th-century Jarl of Orkney. He was the youngest of five sons of Jarl Sigurd Hlodvirsson and the only one resulting from Sigu ...

. In fact, Þórfinnr appears to have been in open conflict with Mac Bethad. This violence may be evidenced by (chronologically suspect) saga-tradition, which appears to indicate that Mac Bethad and his father warred with Orcadian earls. Saga-tradition may also reveal that Echmarcach suffered from Þórfinnr's military advances. For example, the thirteenth-century '' Orkneyinga saga'' states that, after Þórfinnr's consolidation of Orkney and Caithness—an action that likely took place after the death of his brother Brúsi—Þórfinnr was active in the Isles, parts of Galloway and Scotland, and even Dublin. The saga also reveals that Brúsi's son, Rǫgnvaldr

Rǫgnvaldr is an Old Norse language, Old Norse name.

People

* Rǫgnvaldr Guðrøðarson (died 1229), King of the Isles

Derived or cognate names

Given names include:

*''Raginald'', German

*''Reginold'', German

*''Ragenold'', German

*''Ragenald'' ...

, arrived in Orkney at a time when Þórfinnr was preoccupied with the after-effects of such campaigns, as it states that he was "much occupied" with men from the Isles and Ireland. Another source, ''Óláfs saga helga'', preserved within the thirteenth-century saga-compilation ''Heimskringla

''Heimskringla'' () is the best known of the Old Norse kings' sagas. It was written in Old Norse in Iceland by the poet and historian Snorre Sturlason (1178/79–1241) 1230. The name ''Heimskringla'' was first used in the 17th century, derived ...

'', claims that Þórfinnr exerted power in Scotland and Ireland, and that he controlled a far-flung lordship which encompassed Orkney, Shetland

Shetland, also called the Shetland Islands and formerly Zetland, is a subarctic archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands and Norway. It is the northernmost region of the United Kingdom.

The islands lie about to the no ...

, and the Hebrides. Further evidence of Þórfinnr's activities in the region may be preserved by ''Þórfinnsdrápa'', composed by the contemporary Icelandic skald Arnórr Þórðarson, which declares that Þórfinnr raided throughout the Irish Sea region as far south as Dublin.

It is possible that Knútr took other actions to contain Orkney. Evidence that Knútr installed Hákon as overlord of the Isles may be preserved by the twelfth-century '' Ágrip af Nóregskonungasǫgum''. The historicity of this event is uncertain, however, and Hákon's authority in the Isles is not attested by any other source. Be that as it may, this twelfth-century text states that Hákon had been sent into the Isles by Óláfr, and that Hákon ruled the region for the rest of his life. The chronology outlined by this source suggests that Hákon left Norway at about the time Óláfr assumed the kingship in 1016. The former is certainly known to have been in Knútr's service soon afterwards in England. One possibility is that Knútr installed Hákon as overlord of Orkney and the Isles in about 1016/1017, before handing him possession of the Earldom of Worcester in about 1017. If this was the case, Hákon would have been responsible for not only a strategic part of the Anglo-Welsh frontier, but also accountable for the far-reaching sea-lanes that stretched from the Irish Sea region to Norway. It seems likely that Knútr was more concerned about Orkney and the Isles, and the security of the sea-lanes around Scotland, than surviving sources let on. Crawford (2013). Hákon's death at sea would have certainly been a cause of concern for Knútr's regime, and could have been directly responsible to the meeting between him and the three kings. If Hákon had indeed possessed overlordship of the Isles, his demise could well have paved the way for Echmarcach's own rise to power. Having come to terms with the three kings, it is possible that Knútr relied upon Echmarcach to counter the ambitions of the Orcadians, who could have attempted to seize upon Hákon's fall and renew their influence in the Isles.

It is possible that Knútr took other actions to contain Orkney. Evidence that Knútr installed Hákon as overlord of the Isles may be preserved by the twelfth-century '' Ágrip af Nóregskonungasǫgum''. The historicity of this event is uncertain, however, and Hákon's authority in the Isles is not attested by any other source. Be that as it may, this twelfth-century text states that Hákon had been sent into the Isles by Óláfr, and that Hákon ruled the region for the rest of his life. The chronology outlined by this source suggests that Hákon left Norway at about the time Óláfr assumed the kingship in 1016. The former is certainly known to have been in Knútr's service soon afterwards in England. One possibility is that Knútr installed Hákon as overlord of Orkney and the Isles in about 1016/1017, before handing him possession of the Earldom of Worcester in about 1017. If this was the case, Hákon would have been responsible for not only a strategic part of the Anglo-Welsh frontier, but also accountable for the far-reaching sea-lanes that stretched from the Irish Sea region to Norway. It seems likely that Knútr was more concerned about Orkney and the Isles, and the security of the sea-lanes around Scotland, than surviving sources let on. Crawford (2013). Hákon's death at sea would have certainly been a cause of concern for Knútr's regime, and could have been directly responsible to the meeting between him and the three kings. If Hákon had indeed possessed overlordship of the Isles, his demise could well have paved the way for Echmarcach's own rise to power. Having come to terms with the three kings, it is possible that Knútr relied upon Echmarcach to counter the ambitions of the Orcadians, who could have attempted to seize upon Hákon's fall and renew their influence in the Isles.

Uí Briain alliance and the conquest of Dublin

Following his meeting with Knútr, Echmarcach appears to have allied himself with the

Following his meeting with Knútr, Echmarcach appears to have allied himself with the Uí Briain

The O'Brien dynasty ( ga, label= Classical Irish, Ua Briain; ga, label=Modern Irish, Ó Briain ; genitive ''Uí Bhriain'' ) is a noble house of Munster, founded in the 10th century by Brian Boru of the Dál gCais (Dalcassians). After becomi ...

, the descendants of Brian Bóruma mac Cennétig, High King of Ireland. In 1032, the eleventh- to fourteenth-century ''Annals of Inisfallen

Annals ( la, annāles, from , "year") are a concise historical record in which events are arranged chronologically, year by year, although the term is also used loosely for any historical record.

Scope

The nature of the distinction between ann ...

'' states that Donnchad mac Briain, King of Munster Donnchadh () is a masculine given name common to the Irish and Scottish Gaelic languages. It is composed of the elements ''donn'', meaning "brown" or "dark" from Donn a Gaelic God; and ''chadh'', meaning "chief" or "noble". The name is also written ...

married the daughter of a certain Ragnall, adding: "hence the saying: 'the spring of Ragnall's daughter'". This woman is elsewhere identified as Cacht ingen Ragnaill

Cacht ingen Ragnaill was the queen of Donnchad mac Briain, from their marriage in 1032 to her death in 1054, when she is styled Queen of Ireland in the Irish annals of the Clonmacnoise group: the Annals of Tigernach and Chronicon Scotorum. Her h ...

. Like Echmarcach himself, Cacht's patronym could be evidence that she was a near relation of the Ragnalls who ruled Waterford, or else a descendant of Ragnall mac Gofraid. She could have therefore been a sister or niece of Echmarcach himself. Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 232; Oram (2000) p. 18.

At about the time of his union with Cacht, Donnchad aspired to become

At about the time of his union with Cacht, Donnchad aspired to become High King of Ireland

High King of Ireland ( ga, Ardrí na hÉireann ) was a royal title in Gaelic Ireland held by those who had, or who are claimed to have had, lordship over all of Ireland. The title was held by historical kings and later sometimes assigned ana ...

. With powerful maritime forces at his command, Echmarcach would have certainly been regarded as an important potential ally. Clear evidence of an alliance between Echmarcach and the Uí Briain exists in the record of a marriage between Echmarcach's daughter, Mór, and Toirdelbach Ua Briain

Toirdhealbhach Ua Briain (old spelling: Toirdelbach Ua Briain), anglicised ''Turlough O'Brien'' (100914 July 1086), was King of Munster and effectively High King of Ireland. A grandson of Brian Bóruma, Toirdelbach was the son of Tadc mac Briain ...

's son, Tadc, preserved by the twelfth-century '' Banshenchas'', a text which records the marriage of Echmarcach's daughter, Mór, to Tadc, son of Toirdelbach Ua Briain

Toirdhealbhach Ua Briain (old spelling: Toirdelbach Ua Briain), anglicised ''Turlough O'Brien'' (100914 July 1086), was King of Munster and effectively High King of Ireland. A grandson of Brian Bóruma, Toirdelbach was the son of Tadc mac Briain ...

. Annalistic evidence of such an alliance is found well into the late eleventh century. In fact, kinship between Echmarcach's descendants and the Uí Briain even led to the accession of one of Echmarcach's maternal grandsons, Domnall mac Taidc

Domnall mac Taidc (died 1115) was the ruler of the Kingdom of the Isles, the Kingdom of Thomond, and perhaps the Kingdom of Dublin as well. His father was Tadc, son of Toirdelbach Ua Briain, King of Munster, which meant that Domnall was a membe ...

, to the kingship of the Isles at about the turn of the twelfth century.

If Echmarcach was a son of Ragnall mac Gofraid, this alliance with the Uí Briain would have been a continuation of amiable relations between the two families. For example, the father of Ragnall mac Gofraid appears to have combined forces with Brian Bóruma in 984, and Ragnall mac Gofraid himself is recorded to have died in Munster, the heartland of the Uí Briain. If, on the other hand, Echmarcach and Cacht were descended from the Waterford dynasty, an alliance between the Uí Briain and this family may have been undertaken in the context of a struggle between the Uí Briain and the Uí Cheinnselaig. The contemporary leader of the latter kindred was Donnchad's principal opponent, Diarmait mac Maíl na mBó, King of Leinster

Diarmuid Ua Duibhne (Irish pronunciation: ) or Diarmid O'Dyna, also known as Diarmuid of the Love Spot, was a demigod, son of Donn and one of the Fianna in the Fenian Cycle of Irish mythology (traditionally set in the 2nd to 4th century). He ...

. Whilst the Uí Briain certainly allied themselves to Cacht and Echmarcach, Diarmait appears to have backed the descendants of Amlaíb Cuarán, a man whose family appear to have opposed Echmarcach at a latter date.

In 1036, Echmarcach replaced Amlaíb Cuarán's son, Sitriuc mac Amlaíb, as King of Dublin. The ''Annals of Tigernach'' specifies that Sitriuc fled overseas as Echmarcach took control. An alliance with Donnchad could explain Echmarcach's success in seizing the kingship from Sitriuc. Although Donnchad and Sitriuc were maternal half-brothers—as both descended from Gormlaith ingen Murchada—Donnchad's hostility towards Sitriuc is demonstrated by the record of a successful attack he led upon the Dubliners in 1026.

Another factor behind Echmarcach's actions against Sitriuc could concern Knútr. Echmarcach's seizure of Dublin occurred only a year after the latter's death in 1035. Downham (2004) pp. 63–65. There appears to be

In 1036, Echmarcach replaced Amlaíb Cuarán's son, Sitriuc mac Amlaíb, as King of Dublin. The ''Annals of Tigernach'' specifies that Sitriuc fled overseas as Echmarcach took control. An alliance with Donnchad could explain Echmarcach's success in seizing the kingship from Sitriuc. Although Donnchad and Sitriuc were maternal half-brothers—as both descended from Gormlaith ingen Murchada—Donnchad's hostility towards Sitriuc is demonstrated by the record of a successful attack he led upon the Dubliners in 1026.

Another factor behind Echmarcach's actions against Sitriuc could concern Knútr. Echmarcach's seizure of Dublin occurred only a year after the latter's death in 1035. Downham (2004) pp. 63–65. There appears to be numismatic

Numismatics is the study or collection of currency, including coins, tokens, paper money, medals and related objects.

Specialists, known as numismatists, are often characterized as students or collectors of coins, but the discipline also includ ...

evidence, annalistic evidence, and charter evidence indicating that Knútr and Sitriuc had cooperated together in terms of trade and military operations in Wales. In contrast to this apparent congeniality, the relationship between Knútr and Echmarcach appears to have been less amiable. In fact, it is possible that Echmarcach's meeting with Knútr may have bound him from taking action against Sitriuc, and that the confusion caused by Knútr's demise may have enabled Echmarcach to exploit the situation by seizing control of the Irish Sea region.

According to a poetic verse composed by the contemporary Icelandic skald Óttarr svarti

Óttarr svarti (“Óttarr the Black”) was an 11th-century Icelandic skald. He was the court poet first of Olof Skötkonung, Óláfr skautkonungr of Sweden, then of Olaf II of Norway, Óláfr Haraldsson of Norway, the Swedish king Anund Jacob and ...

, Knútr's subjects included Danes

Danes ( da, danskere, ) are a North Germanic ethnic group and nationality native to Denmark and a modern nation identified with the country of Denmark. This connection may be ancestral, legal, historical, or cultural.

Danes generally regard t ...

, Englishmen

The English people are an ethnic group and nation native to England, who speak the English language, a West Germanic language, and share a common history and culture. The English identity is of Anglo-Saxon origin, when they were known in O ...

, Irishmen

The Irish ( ga, Muintir na hÉireann or ''Na hÉireannaigh'') are an ethnic group and nation native to the island of Ireland, who share a common history and culture. There have been humans in Ireland for about 33,000 years, and it has bee ...

, and Islesmen. These Islanders could refer to either the folk of the Isles or Orkney, whilst the Irish seems to refer to the Dubliners. Although the poet's implication that Knútr possessed authority over Sitriuc is not corroborated by any other source, and may therefore be poetic hyperbole, the fact that Sitriuc had been able to undertake a pilgrimage and return home to an intact kingdom in 1028 may demonstrate the extent of influence that Knútr held over the Irish Sea region. This authority, and Sitriuc's apparent close connections with Knútr, could account for the security Sitriuc enjoyed during Knútr's reign.

If Echmarcach was a member of the Waterford dynasty, his action against Sitriuc may have been undertaken in the context of continuous dynastic strife between Dublin and Waterford in the tenth- and eleventh centuries. This could mean that Echmarcach's expulsion of Sitriuc was a direct act of vengeance for the latter's slaying of Ragnall ua Ímair (then King of Waterford) the year before.

Little is known of Echmarcach's short reign in Dublin other than an attack on

If Echmarcach was a member of the Waterford dynasty, his action against Sitriuc may have been undertaken in the context of continuous dynastic strife between Dublin and Waterford in the tenth- and eleventh centuries. This could mean that Echmarcach's expulsion of Sitriuc was a direct act of vengeance for the latter's slaying of Ragnall ua Ímair (then King of Waterford) the year before.

Little is known of Echmarcach's short reign in Dublin other than an attack on Skryne

Skryne or Skreen (), is a village situated on and around a hill between the N2 and N3 national primary roads in County Meath, Ireland. It is situated on the far side of the Gabhra valley from the Hill of Tara. This valley is sometimes referre ...

and Duleek

Duleek (; ) is a small town in County Meath, Ireland.

Duleek takes its name from the Irish word ''daimh liag'', meaning house of stones and referring to an early stone-built church, St Cianán's Church, the ruins of which are still visible in Du ...

, recorded by the seventeenth-century ''Annals of the Four Masters

The ''Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland'' ( ga, Annála Ríoghachta Éireann) or the ''Annals of the Four Masters'' (''Annála na gCeithre Máistrí'') are chronicles of medieval Irish history. The entries span from the Deluge, dated as 2,24 ...

'' in 1037. This strike could have been undertaken in the context of the Dubliner's gradual loss of power in Brega

Brega , also known as ''Mersa Brega'' or ''Marsa al-Brega'' ( ar, مرسى البريقة , i.e. "Brega Seaport"), is a complex of several smaller towns, industry installations and education establishments situated in Libya on the Gulf of Sidra, ...

, and an attempt to regain authority of Skryne. Although there is no direct evidence that Echmarcach controlled Mann at this point in his career, Sitriuc does not appear to have taken refuge on the island after his expulsion from Dublin. This seems to suggest that the island was outwith Sitriuc's possession, and may indicate that Mann had fallen into the hands of Echmarcach sometime before. In fact, it is possible that Echmarcach may have used the island to launch his takeover of Dublin.

Strife in the Isles, Ireland, and Wales

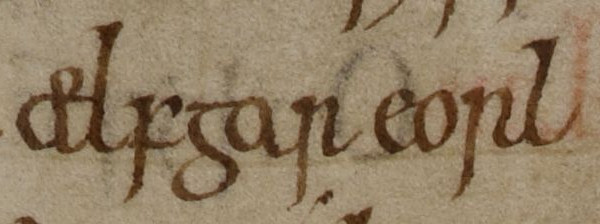

Ímar mac Arailt

Ímar mac Arailt (died 1054) was an eleventh-century ruler of the Kingdom of Dublin and perhaps the Kingdom of the Isles. He was the son of a man named Aralt, and appears to have been a grandson of Amlaíb Cuarán, King of Northumbria and Dubli ...

succeeded Echmarcach as King of Dublin that year—appears to indicate that Echmarcach had been forced from the kingship. Ímar appears have been a descendant (possibly a grandson) of Amlaíb Cuarán, and thus a close relative of the latter's son, Sitriuc, whom Echmarcach drove from the kingship only two years before. It is possible that Ímar received some form of support from Knútr's son and successor in England, Haraldr Knútsson, King of England. The latter was certainly in power when Ímar replaced Echmarcach, and an association between Ímar and Haraldr Knútsson could explain why the ''Annals of Ulster'' reports the latter's death two years later. The fact that Ímar proceeded to campaign in the North Channel North Channel may refer to:

*North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland)

*North Channel (Ontario), body of water along the north shore of Lake Huron, Canada

*North Channel, Hong Kong

*Canal du Nord, France

{{geodis ...

could indicate that Echmarcach had held power in this region before his acquisition of Mann and Dublin. Whatever the case, Ímar's reign lasted only eight years. In 1046, the ''Annals of the Four Masters'' records that he was expelled by Echmarcach, who was then elected king by the Dubliners. The ''Annals of Tigernach'', on the other-hand, simply state that Echmarcach succeeded Ímar.

Echmarcach may well have controlled Mann throughout his second reign in Dublin. Silver hoard

A hoard or "wealth deposit" is an archaeological term for a collection of valuable objects or artifacts, sometimes purposely buried in the ground, in which case it is sometimes also known as a cache. This would usually be with the intention of ...

s uncovered on Mann, dated by their coins to the years 1030s–1050s, may well be the by-product of the intense conflict over control of the island. There is evidence indicating that, at some point in the early eleventh century Hudson, BT (2005) pp. 137–138.—perhaps in the 1020s–1030s—a mint

MiNT is Now TOS (MiNT) is a free software alternative operating system kernel for the Atari ST system and its successors. It is a multi-tasking alternative to TOS and MagiC. Together with the free system components fVDI device drivers, XaA ...

may have developed and functioned on Mann. Coins that appear to have been minted on the island roughly coincide with Echmarcach's rule. These coins are very similar to those produced in Dublin, and may be evidence that Echmarcach attempted to harmonise the coinage utilised within his realm. The production of coins on Mann appears to be evidence of a sophisticated economy in the Isles. In fact, the wealth and sophistication of commerce in Echmarcach's realm could in part explain why the constant struggle for control of Dublin and the Isles was so bitter, and could account for Þórfinnr's apparent presence in the region.

During his second reign, Echmarcach may have been involved in military activities in Wales with Gruffudd ap Rhydderch. For instance in the year 1049, English and Welsh sources record that Norse-Gaelic forces were utilised by Gruffudd ap Rhydderch against his Welsh rivals and English neighbours. Specifically, the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'', the thirteenth- and fourteenth-century ''

During his second reign, Echmarcach may have been involved in military activities in Wales with Gruffudd ap Rhydderch. For instance in the year 1049, English and Welsh sources record that Norse-Gaelic forces were utilised by Gruffudd ap Rhydderch against his Welsh rivals and English neighbours. Specifically, the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'', the thirteenth- and fourteenth-century ''Brut y Tywysogyon

''Brut y Tywysogion'' ( en, Chronicle of the Princes) is one of the most important primary sources for Welsh history. It is an annalistic chronicle that serves as a continuation of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s ''Historia Regum Britanniae''. ''Br ...

'', and the twelfth-century '' Chronicon ex chronicis'' record that a Norse-Gaelic fleet sailed up the River Usk

The River Usk (; cy, Afon Wysg) rises on the northern slopes of the Black Mountain (''y Mynydd Du''), Wales, in the westernmost part of the Brecon Beacons National Park. Initially forming the boundary between Carmarthenshire and Powys, it fl ...

, and ravaged the surrounding region. These sources further reveal that Gruffudd ap Rhydderch and his Norse-Gaelic allies later surprised and routed the English forces of Ealdred, Bishop of Worcester.

Since Echmarcach's extensive ''imperium

In ancient Rome, ''imperium'' was a form of authority held by a citizen to control a military or governmental entity. It is distinct from ''auctoritas'' and ''potestas'', different and generally inferior types of power in the Roman Republic an ...

'' appears to have spanned the Irish Sea region, it is possible that he was regarded as a threat by Siward, Earl of Northumbria

Siward ( or more recently ) or Sigurd ( ang, Sigeweard, non, Sigurðr digri) was an important earl of 11th-century northern England. The Old Norse nickname ''Digri'' and its Latin translation ''Grossus'' ("the stout") are given to him by near-c ...

. Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) pp. 206–207; Oram (2000) p. 34. There is reason to suspect that, by the mid eleventh century, this Anglo-Danish magnate extended his authority into what had previously been the Kingdom of Strathclyde

Strathclyde (lit. "Strath of the River Clyde", and Strað-Clota in Old English), was a Brittonic successor state of the Roman Empire and one of the early medieval kingdoms of the Britons, located in the region the Welsh tribes referred to as Yr ...

. Echmarcach's apparent descent from the Uí Ímair—a dynasty that once reigned over York as kings—combined with Echmarcach's accumulation of power after Knútr's demise, could well have been a cause of concern to the York-based earl. Such unease could partly account for Siward's extension of power into the Solway region, a sphere of insecure territory which may have been regarded as vulnerable by Echmarcach.

Downfall in Dublin and Mann

In 1052, Diarmait drove Echmarcach from Dublin. Wadden (2015) p. 32; Charles-Edwards (2013) pp. 528, 564, 573; Downham (2013a) p. 164; Duffy (2006) p. 55; Hudson, B (2005); Hudson, BT (2004a); Duffy (2002) p. 53; Duffy (1998) p. 76; Duffy (1997) p. 37; Duffy (1993a) p. 32; Duffy (1993b); Duffy (1992) pp. 94, 96–97; Candon (1988) pp. 399, 401; Anderson (1922a) pp. 590–592 n. 2. The event is documented by the ''Annals of the Four Masters'', the ''Annals of Tigernach'', the ''Annals of Ulster'', and ''Chronicon Scotorum''. These annalistic accounts indicate that, although Diarmait's conquest evidently began with a mere raid upon Fine Gall, this action further escalated into the seizure of Dublin itself. Following several skirmishes fought around the town's central fortress, the aforesaid accounts report that Echmarcach fled overseas, whereupon Diarmait assumed the kingship. With Diarmait's conquest, Norse-Gaelic Dublin ceased to be an independent power in Ireland; and when Diarmait and his son, Murchad, died about twenty years later, Irish rule had been exercised over Fine Gall and Dublin in a degree unheard of before. In consequence of Echmarcach's expulsion, Dublin effectively became the provincial capital of Leinster, with the town's remarkable wealth and military power at Diarmait's disposal.

In 1052, Diarmait drove Echmarcach from Dublin. Wadden (2015) p. 32; Charles-Edwards (2013) pp. 528, 564, 573; Downham (2013a) p. 164; Duffy (2006) p. 55; Hudson, B (2005); Hudson, BT (2004a); Duffy (2002) p. 53; Duffy (1998) p. 76; Duffy (1997) p. 37; Duffy (1993a) p. 32; Duffy (1993b); Duffy (1992) pp. 94, 96–97; Candon (1988) pp. 399, 401; Anderson (1922a) pp. 590–592 n. 2. The event is documented by the ''Annals of the Four Masters'', the ''Annals of Tigernach'', the ''Annals of Ulster'', and ''Chronicon Scotorum''. These annalistic accounts indicate that, although Diarmait's conquest evidently began with a mere raid upon Fine Gall, this action further escalated into the seizure of Dublin itself. Following several skirmishes fought around the town's central fortress, the aforesaid accounts report that Echmarcach fled overseas, whereupon Diarmait assumed the kingship. With Diarmait's conquest, Norse-Gaelic Dublin ceased to be an independent power in Ireland; and when Diarmait and his son, Murchad, died about twenty years later, Irish rule had been exercised over Fine Gall and Dublin in a degree unheard of before. In consequence of Echmarcach's expulsion, Dublin effectively became the provincial capital of Leinster, with the town's remarkable wealth and military power at Diarmait's disposal.

The fact that in 1054, Ímar mac Arailt is styled on his death "''rí Gall''", a title meaning "king of the foreigners", could indicate that Diarmait reinserted him as King of Dublin after Echmarcach's expulsion. Murchad appears to have been granted the kingship by 1059, as evidenced by the title ''tigherna Gall'', meaning "lord of the foreigners", accorded to him that year. Murchad was evidently an energetic figure, and in 1061 he launched a successful seaborne invasion of Mann. The ''Annals of the Four Masters'', and the ''Annals of Tigernach'' further reveal that Murchad extracted a tax from Mann, and that the son of a certain Ragnall (literally "''mac Raghnaill''" and "''mac Ragnaill''") was driven from the island. The gathering of ''cáin'' or tribute was a mediaeval right of kingship in Ireland. In fact, Murchad's collection of such tribute from the Manx could be evidence that, as the King of Dublin, Murchad regarded himself as the rightful overlord of Mann. If the vanquished son of Ragnall was Echmarcach himself, as seems most likely, the record of Murchad's actions against him would appear to indicate that Echmarcach had seated himself on the island after his expulsion from Dublin. Another possibility is that Echmarcach had only been reestablished himself as king in the Isles after Ímar mac Arailt's death in 1054.

The fact that in 1054, Ímar mac Arailt is styled on his death "''rí Gall''", a title meaning "king of the foreigners", could indicate that Diarmait reinserted him as King of Dublin after Echmarcach's expulsion. Murchad appears to have been granted the kingship by 1059, as evidenced by the title ''tigherna Gall'', meaning "lord of the foreigners", accorded to him that year. Murchad was evidently an energetic figure, and in 1061 he launched a successful seaborne invasion of Mann. The ''Annals of the Four Masters'', and the ''Annals of Tigernach'' further reveal that Murchad extracted a tax from Mann, and that the son of a certain Ragnall (literally "''mac Raghnaill''" and "''mac Ragnaill''") was driven from the island. The gathering of ''cáin'' or tribute was a mediaeval right of kingship in Ireland. In fact, Murchad's collection of such tribute from the Manx could be evidence that, as the King of Dublin, Murchad regarded himself as the rightful overlord of Mann. If the vanquished son of Ragnall was Echmarcach himself, as seems most likely, the record of Murchad's actions against him would appear to indicate that Echmarcach had seated himself on the island after his expulsion from Dublin. Another possibility is that Echmarcach had only been reestablished himself as king in the Isles after Ímar mac Arailt's death in 1054.

Magnús Haraldsson and Ælfgar Leofricson

In 1055, after being outlawed for treason in the course of a comital power-struggle, English nobleman Ælfgar Leofricson fled from England to Ireland. Ælfgar evidently received considerable military aid from the Irish to form a fleet of eighteen ships, and together with Gruffudd ap Llywelyn, King of Gwynedd and Deheubarth invaded

In 1055, after being outlawed for treason in the course of a comital power-struggle, English nobleman Ælfgar Leofricson fled from England to Ireland. Ælfgar evidently received considerable military aid from the Irish to form a fleet of eighteen ships, and together with Gruffudd ap Llywelyn, King of Gwynedd and Deheubarth invaded Herefordshire

Herefordshire () is a county in the West Midlands of England, governed by Herefordshire Council. It is bordered by Shropshire to the north, Worcestershire to the east, Gloucestershire to the south-east, and the Welsh counties of Monmouthshire ...

.

Although this campaign ultimately secured Ælfgar's reinstatement, Ælfgar (then Earl of Mercia

Earl of Mercia was a title in the late Anglo-Saxon, Anglo-Danish, and early Anglo-Norman period in England. During this period the earldom covered the lands of the old Kingdom of Mercia in the English Midlands.

First governed by ealdormen under t ...

) was again exiled from England in 1058, and proceeded to ally himself with Gruffudd ap Llywelyn and a Norse fleet. Notwithstanding the fact that Scandinavian sources fail to report this operation, the ''Annals of Tigernach'' reveals that the leader of the fleet was Magnús, son of Haraldr Sigurðarson, King of Norway, and further reports that Magnús' forces were composed of Orcadians, Islesmen, and Dubliners.

Exactly who Ælfgar received aid from in the Irish Sea region is uncertain. It is conceivable that, after his flight from England in 1055, Ælfgar was outfitted in Dublin, then ruled by Murchad (with Diarmait as overlord). Likewise, since Diarmait's forces had previously driven Echmarcach from Dublin in 1052, and apparently from Mann in 1061, the joint campaign of Ælfgar and Magnús in 1058—which utilised Islesmen and Dubliners—could well have involved Diarmait's cooperation as well. That being said, there are several reasons to doubt a part played by Diarmait in Ælfgar's military undertakings. For instance, Diarmait seems to have lent assistance to Ælfgar's enemies— the Godwinsons—in the 1050s and 1060s. Diarmait also appears to have previously backed Cynan ab Iago

Cynan ab Iago (c. 1014 c. 1063) was a Welsh prince of the House of Aberffraw sometimes credited with briefly reigning as King of Gwynedd. His father, Iago ab Idwal ap Meurig, had been king before him and his son, Gruffudd, was king after him.

I ...

, a man who was a bitter rival and seemingly the eventual slayer of Ælfgar's ally and son-in-law, Gruffudd ap Llywelyn.

Ælfgar's Irish confederate of 1055 is not identified in any source, and it is not clear that Diarmait had a part to play in the aforesaid events of that year. In fact, it is possible that Ælfgar received aid not from Diarmait, but from Donnchad—Diarmait's enemy and Echmarcach's associate—a man who then controlled the Norse-Gaelic enclaves of

Ælfgar's Irish confederate of 1055 is not identified in any source, and it is not clear that Diarmait had a part to play in the aforesaid events of that year. In fact, it is possible that Ælfgar received aid not from Diarmait, but from Donnchad—Diarmait's enemy and Echmarcach's associate—a man who then controlled the Norse-Gaelic enclaves of Limerick

Limerick ( ; ga, Luimneach ) is a western city in Ireland situated within County Limerick. It is in the province of Munster and is located in the Mid-West which comprises part of the Southern Region. With a population of 94,192 at the 2016 ...

and possibly Waterford. Furthermore, although Diarmait appears to have gained overlordship of Mann by 1061, Echmarcach presumably enjoyed overlordship of at least part of the Hebrides in 1058. Since Magnús utilised Islesmen during his English campaign of that year, it is conceivable that Echmarcach may have played a prominent part in these operations. If Echmarcach was indeed involved in the campaign, the enmity between him and Diarmait could indicate that these two were unlikely to have cooperated as allies.